Ken Knabb, editor and translator of The Situationist International Anthology, among other works, has posted an interesting essay about the COVID-19 crisis and its effects on us at his website, Bureau of Public Secrets:

We come to realize how much we miss certain things, but also that there are things we don’t miss. Many people have noted (usually with a half-guilty hesitation, since they are of course quite aware of the devastation that is going on in many other people’s lives) that they personally are appreciating the experience in some regards. It’s much quieter, the skies are clearer, there’s scarcely any traffic, fish are returning to formerly polluted waterways, in some cities wild animals are venturing into the empty streets. There has been much joking about how those who like quiet contemplative living are hardly noticing any difference, in contrast to the frustrations and anxieties of those who are used to more gregarious lifestyles. In any case, whether they like it or not, millions of people are getting a crash course in cloistered living, with repeated daily schedules almost like monks in a monastery. They may continue to distract themselves with entertainments, but the reality keeps bringing them back to the present moment.

I suspect that the frantic urgency of various political leaders to get things “back to normal” as soon as possible is not only for the ostensible economic reasons, but also because they dimly sense that the longer this pause goes on, the more people will become detached from the addictive consumer pursuits of their previous lives and the more they will be open to exploring new possibilities.

“Pregnant Pause — Remarks on the Corona Crisis”

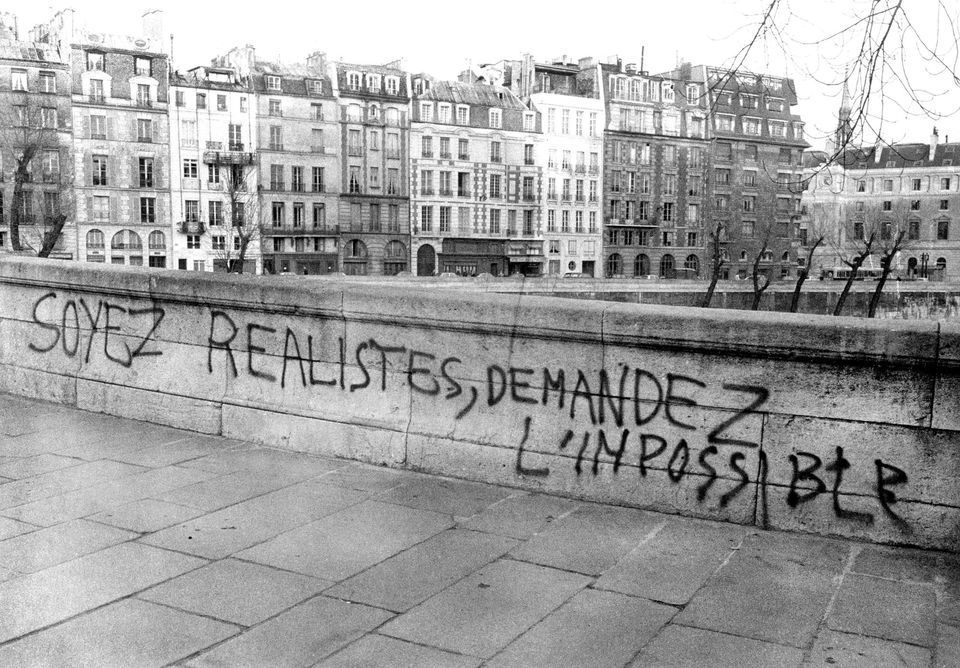

I have no idea what will happen next, and make no predictions, but it is remarkable how much of what was “normal” or “common sense” back in early March seems like ancient history—or insanity—now. Even capitalist newspapers like the Financial Times have been talking about establishing universal basic income, a mostly fringe idea back when Occupy Wall Street was happening, nine years ago.

Earlier today I had the thought that the current crisis was making me realize that the punks of my teens and twenties, who were ignored or disdained by “serious” people, had been basically correct about everything: the state is corrupt, corporations are bad, factory farming kills (animals and us), local mutual aid is preferable to international logistics and supply lines, living cheaply and cooperatively can lead to a richer life, etc. Which I guess means it’s time for me, in my late forties, to become a bicycle-riding vegan anarchist, get a part-time job at a co-op, start a ‘zine or a band, serve free food in public parks, etc.!